On Thursday January 18th, I was looking at the newspaper and the latest news sport header read: “football career ends after concussion: ‘Good guidance’ was missing”. A Dutch female football player got a ball against her head and little did she know that the ball against her head would change her life forever. In 2008 she suffered from both a concussion and a whiplash injury. However, she continued to play, but after a few days her complaints remained. At the club she alarmed her coach and the medical staff. Too late it turns out. She did not recover according to expectations, enforcing her to bury her dreams and end her career.

Both concussion and whiplash injury are a significant cause of morbidity, with many survivors dealing with persisting difficulties for years post injury. In most cases, full recovery is expected within 3 months after concussion/whiplash injury. Yet, not all patients experience such rapid recovery. Up to 15% of patients diagnosed with concussion and up to 50% of patients diagnosed with whiplash injury continue to experience persistent disabling symptoms (Marshall et al, 2015 ; De Kooning et al, 2015). A number of factors influence the rate and extent of recovery is such as the mechanism and setting for the initial injury. Sterling 2014 presented prognostic factors showing consistent evidence for poor recovery after whiplash injury. In both injuries, a correct diagnosis is a critical step in successful management leading to improved outcomes and a decreased potential delay in recovery. However, diagnosis of these injuries is often difficult for the practitioner and frustrating for the patient.

In this blogpost, I made a comparison between post-concussion syndrome (PCS) and whiplash associated disorder (WAD), in an attempt to answer the question that came to my mind: “Is it clear for the practitioner, on how to do a correct diagnosis of PCS and WAD?”

Before even trying to find an answer on this question, I asked myself another question. Is there already a clear definition of PCS and WAD?

Surrounding the definition of PCS there is much confusion. The Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation Guideline for Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury & Persistent Symptoms (2nd edition, 2008) stated: “Just as there is confusion surrounding the definition of mild traumatic brain injury, this is also the case with the definition of PCS”. While Voormolen et al, 2018 stated: “It is challenging to define PCS because there is no consensus with regards to the criteria for diagnosis. The most used criteria for diagnosis are those specified in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV).”

PCS is best defined as: the persistence of three or more symptoms for 4 weeks (ICD-10), or 3 months (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - DSM IV), following a concussion – a mild form of traumatic brain injury.

Diagnostic criteria of PCS as offered by the ICD-10:

Is the definition of WAD more clear than the definition of PCS?

The Quebec Task Force developed recommendations regarding the classification and treatment of WAD, which were used to develop a guide for managing whiplash 1995. In this guide Spitzer and colleagues, 1995 defined whiplash injury as: bony or soft tissue injuries resulting from rear-end or side impact, predominantly in motor vehicle accidents, and from other mishaps as a result of an acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer to the neck. The impact may lead to a variety of clinical manifestations called WAD. In this case, I believe it is safe to say that an unambiguous definition is still missing for WAD.

Diagnosis of PCS vs WAD

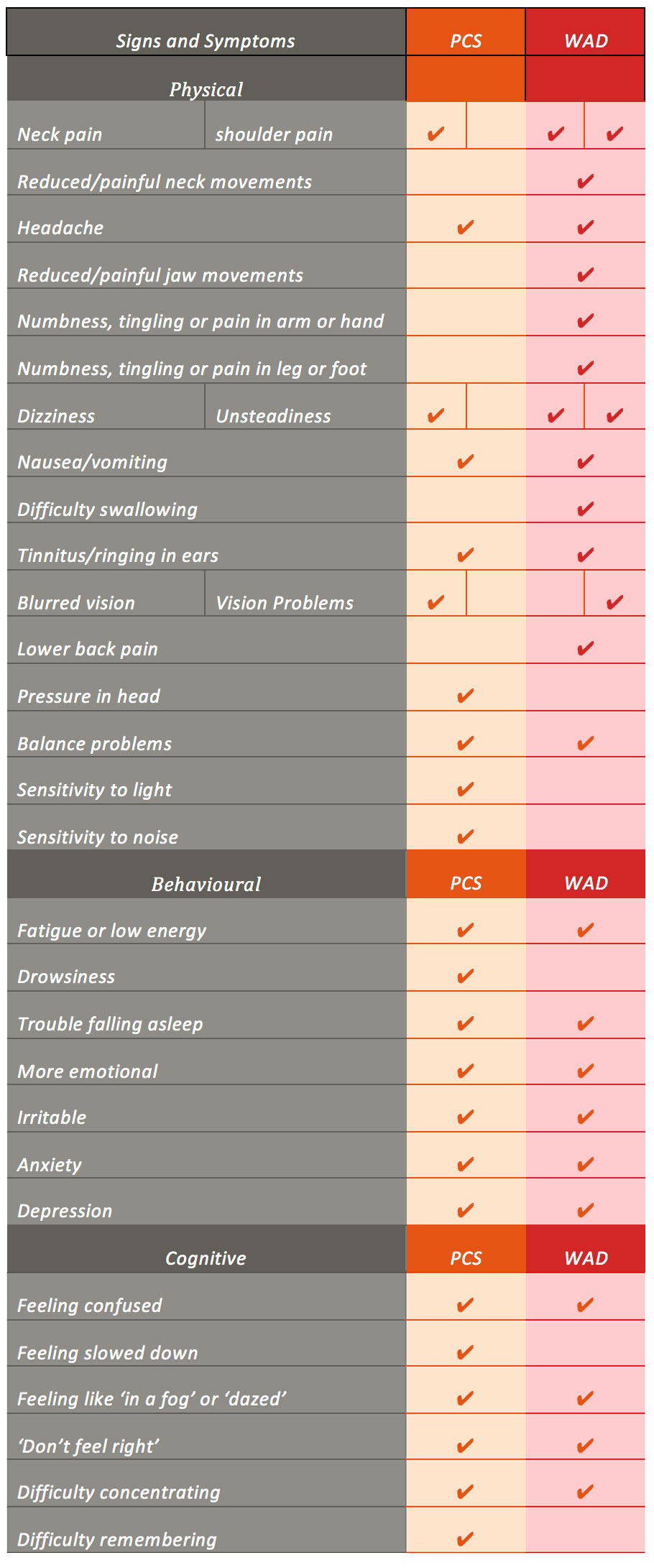

The fact that it is challenging to define PCS and WAD, makes it also challenging to diagnose. In addition, many controversies regarding the diagnosis of PCS and WAD exist because of 1) the wide variety in number of patients reporting injury, 2) the inability in many cases to find firm diagnostic evidence of injury and 3) the studies examining PCS and WAD, which have reported significant signs and symptom overlap with other diagnoses that can result as a consequence of a traumatic experience, for example, post-traumatic stress disorder and post traumatic headache. Patients with WAD have reported signs and symptoms that appear strikingly similar to those experienced in PCS, with the exception of a few key differences (i.e. radicular symptoms) (Table 1).

This is where the shoe pinches. Both the diagnosis of PCS and WAD have changed little in recent times and remain rather clinical (Sterling 2014). The diagnosis of WAD is made on the mechanism of the injury and patient reported symptoms – neck pain and related symptoms following a traumatic event, usually a road traffic crash. The diagnosis of PCS is based on a constellation of symptoms commonly experienced following mild traumatic brain injury. There are no specific neuropsychological tests that can diagnose PCS or WAD (Marshall et al, 2015 ; Rodriquez et al, 2004). Also, in the case of WAD, current clinical guidelines recommend that radiological imaging should be undertaken only to detect WAD grade IV (ie, fracture or dislocation) and that clinicians should adhere to the Canadian C-Spine rule or Nexus rule when making the decision to refer the patient for radiographic examination (Nikles et al, 2017).

Hence, it is very difficult for practitioners to differentiate between PCS and WAD and perform a correct diagnosis. They have to rely heavily on patient reported signs and symptoms, which as mentioned earlier, show significant overlap (Table 1) and are even common in normal populations (Iverson & Lange, 2003). Aditionally, surveys of general practitioners in Canada (Ferrari et al,2004) and Australia (Brijnath et al, 2016) have shown, that general practitioners often lack knowledge about WAD and confidence in injury diagnosing and management. Training and educating general practitioners has the potential to reduce unnecessary imaging for WAD and optimise diagnosis and early referral of patients at risk of delayed recovery.

Regardless of formal diagnosis (e.g., PCS versus WAD), symptoms following concussion/whiplash injury have the potential to cause limitations and need to be addressed in a coordinated and directed way in order to assist recovery. It is mandatory that pain and disability be measured as the first step of clinical assessment due to their consistent prognostic capacity. For whiplash injury, guideline-recommended pain measures include the 11-point visual analogue scale or numeric rating scale, and the recommended measure of disability is the Neck Disability Index due its clinimetric properties (Nikles et al, 2017). However, other measures are also acceptable, and some include the Whiplash Disability Questionnaire and the Patient Specific Functional Scale (Nikles et al, 2017). A valid assessment tool for concussion is the Rivermead Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire

It is also important to note that there is frequently interplay of symptoms, social circumstances, and subsequent development of complications (e.g., anxiety, stress) that can complicate and negatively influence recovery. The particular cluster of symptoms will vary among patients, necessitating an individualized approach to management.

Have your say:

“Do Physiotherapists need to take a greater role in the overall care plan of the patient with whiplash associated disorder or post-concussion syndrome? This would mean, having expertise in the assessment of risk factors and an understanding of when additional treatments such as medication and psychological interventions are required.”

Vote: https://goo.gl/X5NpQr

Results: https://goo.gl/3KVK3K

Table 1. A comparison of signs and symptoms of PCS and WAD. from the post-concussion symptom score of the Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool version 3 (SCAT-3), the WAD Form C of the Quebec Task Force for Whiplash Associated Disorder (Spitzer et al, 1995) and findings of systematic reviews on PCS and WAD.

Ward Willaert

Ward Willaert is a doctoral researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Brussels, Belgium) and Ghent university (Ghent, Belgium). He is a member of the Pain in Motion research group and his research and clinical interest goes out to chronic "unexplained" pain, associated disorders, diagnosis and treatment of (chronic) pain. He has a special interest in whiplash associated disorders and the central nervous system.

2018 Pain in Motion

References and further reading:

Marshall, S. et al. Updated clinical practice guidelines for concussion/mild traumatic brain injury and persistent symptoms. Brain Inj. 29, 688–700 (2015).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25871303

Kooning, M. De et al. Endogenous pain inhibition is unrelated to autonomic responses in acute whiplash-associated disorders. 52, 431–440 (2015).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26348457

Sterling, M. Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). J. Physiother. 60, 5–12 (2014).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24856935

Voormolen, D. C. et al. Divergent Classification Methods of Post-Concussion Syndrome after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Prevalence Rates, Risk Factors and Functional Outcome. J. Neurotrauma neu.2017.5257 (2018). doi:10.1089/neu. 2017 .5257

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29350085

Bigler ED. Neuropsychology and clinical neuroscience of persistent post-concussion syndrome. 14, 1-22 (2008)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18078527

Spitzer, W. O. et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976). 20, 1S–73S (1995)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7604354

Rodriquez, A. A., Barr, K. P. & Burns, S. P. Whiplash: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Muscle Nerve 29, 768–781 (2004).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15170609

Nikles, J., Yelland, M., Bayram, C., Miller, G. & Sterling, M. Management of Whiplash Associated Disorders in Australian general practice. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 18, 551 (2017)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5747169/

Iverson, G. L. & Lange, R. T. Examination of “Postconcussion-Like” Symptoms in a Healthy Sample. Appl. Neuropsychol. 10, 137–144 (2003)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12890639

Ferrari, R. & Russell, A. S. Survey of general practitioner, family physician, and chiropractor’s beliefs regarding the management of acute whiplash patients. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976). 29, 2173–7 (2004).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15454712

Brijnath, B. et al. General practitioners knowledge and management of whiplash associated disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder : implications for patient care. BMC Fam. Pract. 1–11 (2016).

https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-016-0491-2