Five Requirements for Effective Pain Neuroscience Education in physiotherapy practice

Pain neuroscience has taught us that pain can be present without tissue damage, is often disproportionate to tissue damage, and that tissue damage (and nociception) does not necessarily result in the feeling of pain. Unfortunately patients are often not aware of these facts and stick more to a biomedical model in which they keep on searching for a structural cause of their pain and consequently the “magic bullet” to solve their problem. This may result in low self-efficacy, unrealistic or inappropriate therapy expectations and huge therapy barriers.

Pain neuroscience education intends to transfer knowledge to chronic pain patients, thus allowing them to understand their pain and create adaptive perceptions and improving their ability to cope with their pain. Pain neuroscience education implies teaching people about the underlying mechanisms of pain, including how the brain produces pain. Much attention is paid to the fact that pain is not always the consequence of damage and that, definitely in case of persistent pain, the pain is due to enhanced central pain processing rather than structural damage.

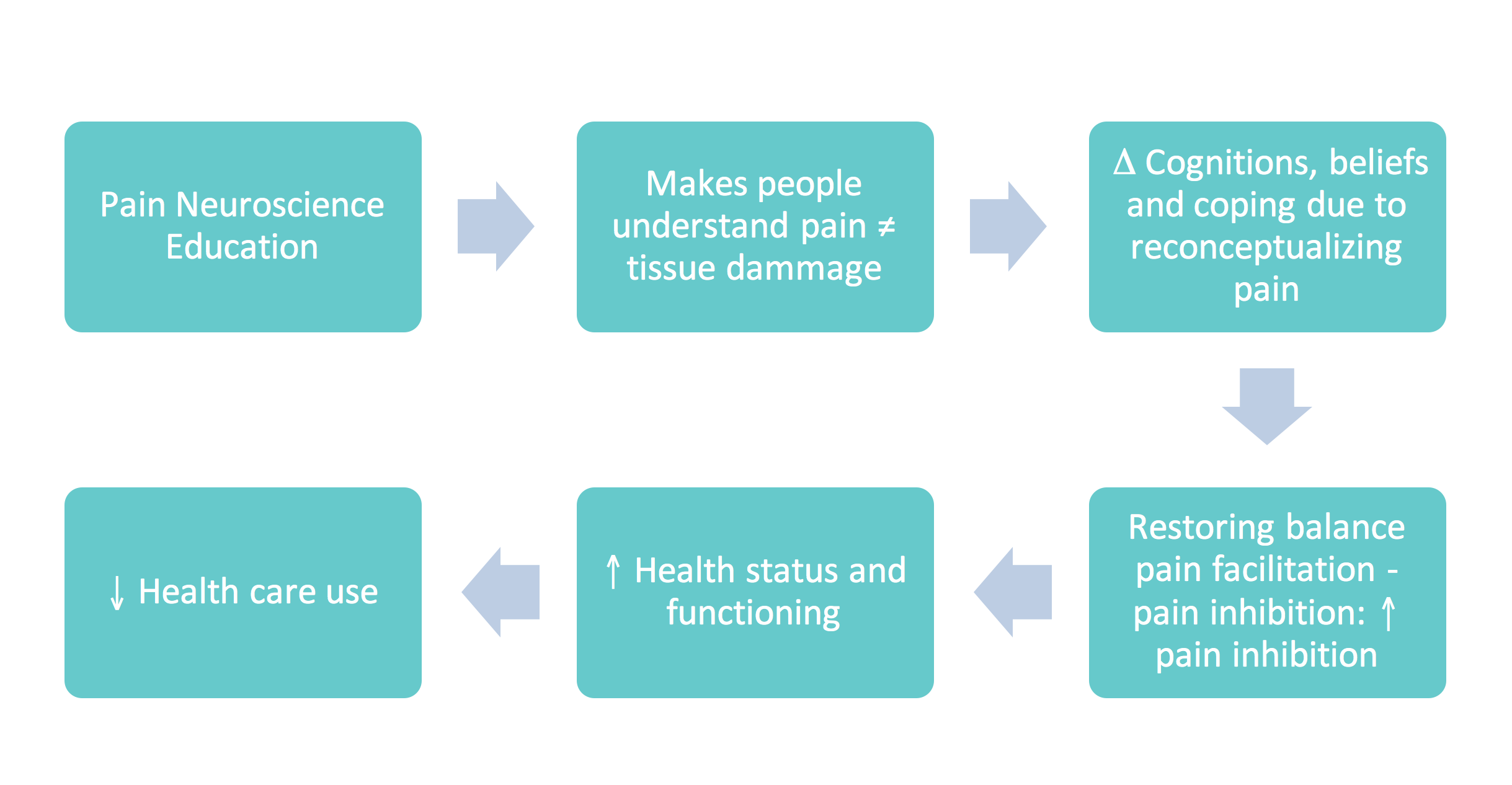

Understanding pain this way, decreases its threat value, leading to more effective pain coping strategies1,2. We and others have shown that pain neuroscience education is effective in changing pain beliefs, improving health status and reducing health care expenditure in adult patients with various chronic pain disorders3-13 (Figure 1). Another amazing finding from a randomized controlled trial of our group5 is the observed effect of pain neuroscience education on endogenous analgesia (measured using the conditioned pain modulation paradigm). Just 2 sessions of pain neuroscience education resulted in improved endogenous pain inhibition in fibromyalgia patients5. Even though the effect size on endogenous analgesia was rather small, the finding provides a powerful message to be delivered during pain neuroscience education to our patients: ‘Research has shown that understanding more about pain in itself results in pain suppression in your body’. This way we can alter the patients’ expectations for care, always an important thing to do when treating patients with chronic pain. Although “acceptance” can be an important part in the therapy as well, it seems that recovery expectations are important prognostic factors regarding therapy outcome. Additionally, providing education is a first step in restoring the balance between pain facilitation and pain inhibition and dampening the pain neuromatrix. Understanding pain is crucial for changing certain pain cognitions (eg. catastrophizing) and these pain cognitions are related to increased brain activity. Pain neuroscience education is a way to reduce the widespread brain activity and to calm down the pain neuromatrix. By retraining the brain we can prime patients for further steps in our treatment approach.

Figure 1: Established effects of therapeutic pain neuroscience education (or ‘brain school’) in chronic pain patients3,5,14.

Thus, level A evidence supports the use of therapeutic pain neuroscience education for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. However, when using it in clinical practice, not all patients reconceptualise their pain easily. Here are 5 (often neglected) requirements for effective pain neuroscience education and some ideas on how clinicians can address them with their patients.

Requirement 1: Interaction with a therapist is necessary to obtain clinically meaningful effects on pain15

Interactions with a therapist is required to impart the desired effects of pain neuroscience education. We conducted a multi-centre trial and it showed how important therapists are for explaining pain neuroscience to chronic pain (fibromyalgia in this study) patients15. As explained above, mounting evidence supports the use of face-to-face pain neuroscience education or communication for the treatment of chronic pain patients. This study examined whether written education about pain neuroscience improves illness perceptions, catastrophizing and health status in patients with fibromyalgia15. Compared to written relaxation training, written pain neuroscience education slightly improved illness perceptions of patients with fibromyalgia, but was not associated with clinically meaningful effects on pain, catastrophizing, or the impact of fibromyalgia on daily life. Our research suggests that face-to-face sessions of pain neuroscience education are required to change inappropriate cognitions and perceived health in patients with fibromyalgia. In that way the therapist can interact with the patient and try to help the patient applying the theory to daily life. Besides explaining the matter with metaphors, it is important that the patient recognizes the concepts and that he can translate it into his individual situation.

Requirement 2: Only patients dissatisfied with their current perceptions about pain are prone to reconceptualization of pain16-18

This implies that therapist should question the patient’s pain perceptions thoroughly prior to commencing pain neuroscience education. Even though their pain perceptions lack medical and scientific validity, patients are often satisfied with them. In such cases, it is necessary to question whether the patient can think of other reasons / underlying mechanisms for their pain rather than lecturing about pain mechanisms. It makes no sense to impose concepts and certain behaviours if the patients does not comply with them or believe in it. As long as the theories remains counterintuitive for the patient it will not be retained and integrated with attitudes and beliefs2. This form of “deep learning” is only possible when the learner is motivated19.

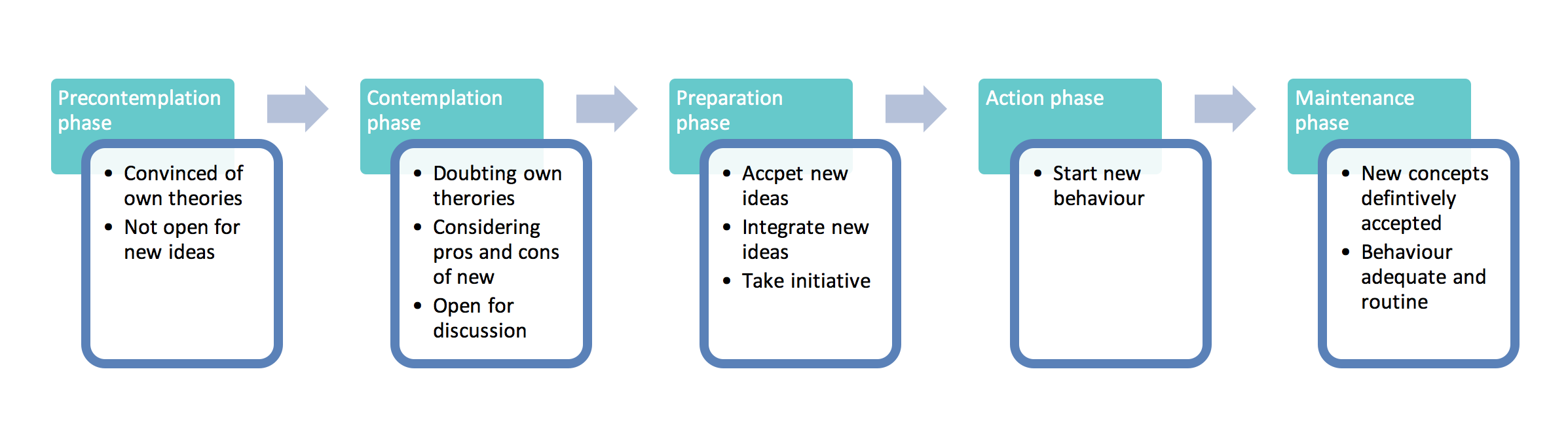

Therefore, before initiating pain neuroscience education, the therapist should lead the patient towards a situation where the patient doubts his or her current pain perceptions. This fits in the model of “stages of change” 20 in which the therapist should try to transfer the patient from the precontemplation stage (not ready) to the contemplation and even the preparation stage.

Figure 2: Stages of change applied to pain neuroscience education (based on4,20,21)

A patient in the precontemplation stage is not open-minded to new theories and a therapist is unlikely to be able to convince such patients to reconceptualise their pain. This may even have adverse effects. It is primordial to let the patient reflect on his own perceptions, in order to create doubts about these.

The following questions may assist therapists in achieving this:

“Can you think of other reasons why you are still having neck pain?”

“I guess up to now searching for the magic bullet to ‘cure’ the damaged disc in your lower spine wasn’t such a big success, was it?”

Requirement 3: Any new explanation must be intelligible to the patient16-18

If the content of the pain neuroscience education is individually-tailored (to the level of intelligence etc.), then this should not be a problem. Still, it is necessary to check whether the patient has understood the pain neuroscience education. Use the neurophysiology of pain test22, (re)question their pain perception, or ask them to explain to you why they are in pain.

Requirement 4: New explanation must appear plausible and beneficial to the patient16-18

Even though the content of pain neuroscience education is backed-up by a body of scientific literature, it should apply to the patient’s situation/pain. For instance, if you include the mechanism of central sensitization in your pain neuroscience education for a particular patient, then you want to be 100% certain that this patient is having a clinical picture dominated by central sensitization (Guidelines on how to recognize central sensitization pain in clinical practice are available23). If not, the patient might not recognize their own situation in the explanation, making it unlikely that the patient will reconceptualise his or her pain. And “deep learning” is again only possible when the information presented is made personally relevant.

To move on in the model of the “stages of change”, it is important that the concept is beneficial for the patient. This means that the patient will only be open to new ideas if they lead to opportunities. Therefore, the pain education should be offered as a physiological explanation for their complaints. As patients often search for a biomedical explanation and the people in a patient’s environment tends to classify the pain more as psychosomatic, pain education builds the bridge in between. It is the confirmation of a real existing problem for which they can be treated in an appropriate way. This recognition gives grip to the patient and may create correct therapy expectations.

Requirement 5: The new explanation should be shared and confirmed by the direct environment of the patient

To reinforce the patient and move on in the change model to the action and maintenance stage, it is important that the patient is supported by relevant others. Therefore, it is important that the new concepts are shared with family and friends. It can be useful to involve a partner in the education sessions, so that they also cope in a correct way with the complaints of the patient.

Finally, the communication with other health care disciplines is crucial. When different disciplines give contradictory opinions and explanations to patients, this is very confusing for the patient and it might be tempting for some patients to fall back on more biomedical “magic bullets” which often require much less effort by the patient.

Clinicians can freely access tools to support their pain neuroscience education on our website: the tools are available in 5 languages including English and French: http://www.paininmotion.be/EN/sem-tools.html. These include power point slides, information booklets, questionnaires and examples of conversations between therapist and patient.

Mira Meeus & Jo Nijs

2016 Pain in Motion

References and further reading:

1. Moseley GL. Unraveling the barriers to reconceptualization of the problem in chronic pain: the actual and perceived ability of patients and health professionals to understand the neurophysiology. J Pain 2003; 4(4): 184-9.

2. Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy 2003; 8(3): 130-40.

3. Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92(12): 2041-56.

4. Nijs J, Paul van Wilgen C, Van Oosterwijck J, van Ittersum M, Meeus M. How to explain central sensitization to patients with 'unexplained' chronic musculoskeletal pain: practice guidelines. Manual Therapy 2011; 16(5): 413-8.

5. Van Oosterwijck J, Meeus M, Paul L, et al. Pain physiology education improves health status and endogenous pain inhibition in fibromyalgia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. The Clinical Journal of Pain 2013; 29(10): 873-82.

6. Van Oosterwijck J, Nijs J, Meeus M, et al. Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: a pilot study. J Rehabil Res Dev 2011; 48(1): 43-58.

7. Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain 2004; 8(1): 39-45.

8. Moseley GL. Widespread brain activity during an abdominal task markedly reduced after pain physiology education: fMRI evaluation of a single patient with chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother 2005; 51(1): 49-52.

9. Moseley GL. Joining forces – combining cognition-targeted motor control training with group or individual pain physiology education: a successful treatment for chronic low back pain. . J Manual Manipulative Ther 2003; 11: 88-94.

10. Moseley GL, Nicholas MK, Hodges PW. A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain 2004; 20(5): 324-30.

11. Moseley GL. Combined physiotherapy and education is efficacious for chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother 2002; 48(4): 297-302.

12. Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative Pain Neuroscience Education for Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Multi-Center Randomized Controlled Trial With One-Year Follow-Up. Spine 2014.

13. Meeus M, Nijs J, Van Oosterwijck J, Van Alsenoy V, Truijen S. Pain physiology education improves pain beliefs in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared with pacing and self-management education: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91(8): 1153-9.

14. Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative Pain Neuroscience Education for Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial With 1-Year Follow-up. Spine 2014; 39(18): 1449-57.

15. van Ittersum MW, van Wilgen CP, van der Schans CP, Lambrecht L, Groothoff JW, Nijs J. Written pain neuroscience education in fibromyalgia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Pain Practice : the Official Journal of World Institute of Pain 2014; 14(8): 689-700.

16. Siemonsma PC, Schroder CD, Dekker JH, Lettinga AT. The benefits of theory for clinical practice: cognitive treatment for chronic low back pain patients as an illustrative example. Disability and Rehabilitation 2008; 30(17): 1309-17.

17. Siemonsma PC, Schroder CD, Roorda LD, Lettinga AT. Benefits of treatment theory in the design of explanatory trials: cognitive treatment of illness perception in chronic low back pain rehabilitation as an illustrative example. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2010; 42(2): 111-6.

18. Siemonsma PC, Stuive I, Roorda LD, et al. Cognitive treatment of illness perceptions in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy 2013; 93(4): 435-48.

19. Sankaran S. Impact of learning strategies and motivation on performance: A study in web-based instruction. Journal of Instructional Psychology 2001; 28(3): 191–8.

20. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Self change processes, self efficacy and decisional balance across five stages of smoking cessation. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research 1984; 156: 131-40.

21. van Wilgen CP, Nijs J. Pijneducatie: een praktische handleiding voor (para)medici: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2010.

22. Moseley L. Unraveling the barriers to reconceptualization of the problem in chronic pain: the actual and perceived ability of patients and health professionals to understand the neurophysiology. J Pain 2003; 4(4): 184-9.

23. Nijs J, Torres-Cueco R, van Wilgen CP, et al. Applying modern pain neuroscience in clinical practice: criteria for the classification of central sensitization pain. Pain Physician 2014; 17(5): 447-57.