INTRODUCTION

The term “whiplash” is given to the acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer to the neck and head at impact. It may result from rear-end or side-impact motor vehicle collisions, but can also occur during sport (horse riding, diving, snowboarding) and other mishaps. The impact may result in physical injury (bony and/or soft-tissue injuries) and/or psychological trauma (distress), which in turn can lead to a variety of clinical manifestations, including neck pain, neck stiffness, headache, dizziness, paresthesias, and cognitive difficulties such as memory loss. These clinical manifestations are known as whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) (Spitzer et al., 1995).

EPIDEMIOLOGY & ECONOMICS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

CLINICAL FEATURES

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

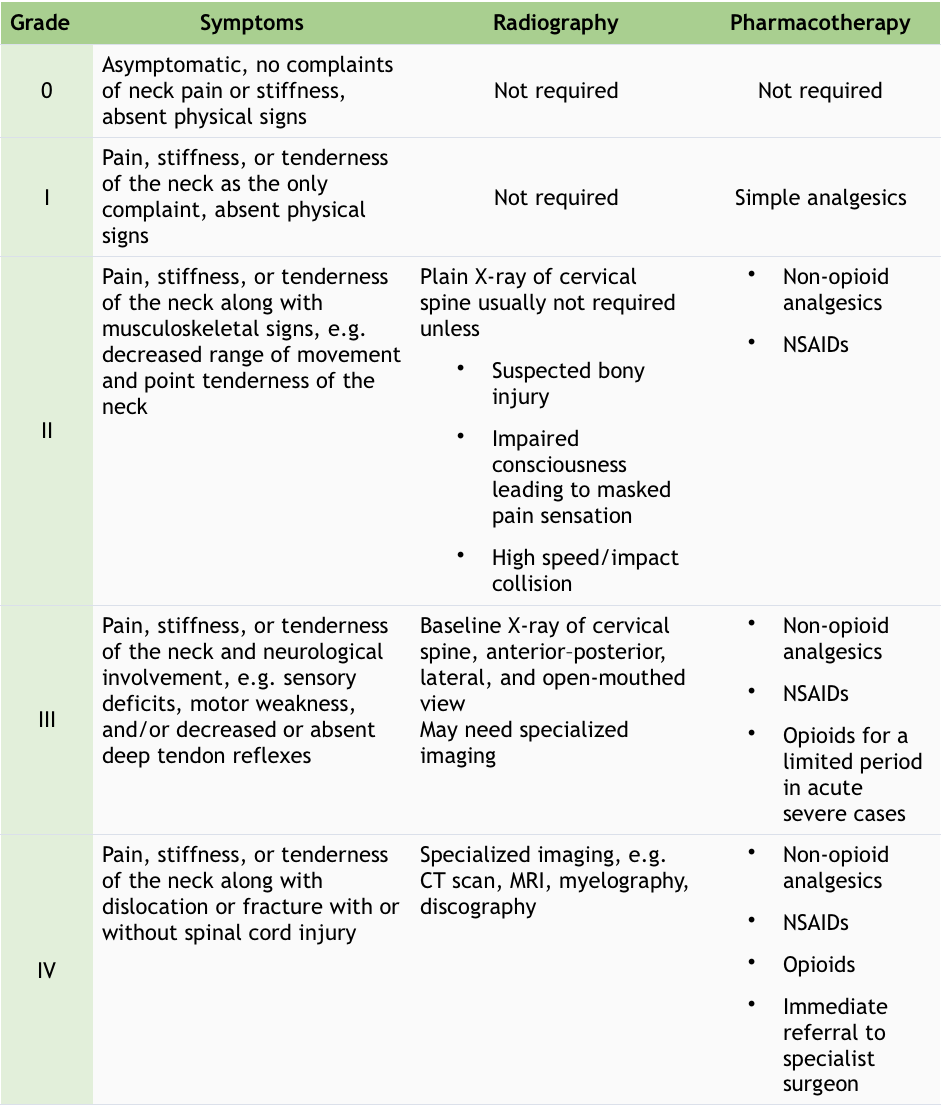

Table 1 Classification of WAD (NICE. Neck pain – whiplash injury; State Insurance Regulatory Authority: Guidelines for the management of acute whiplash-associated disorders – for health professionals. Sydney: third edition.," 2014)

TREATMENT

Whiplash injuries are quite difficult to treat because of interactions of various factors such as patient psychology, socioeconomic factors, legal issues, and physical health. The absence of radiological evidence of injury in the symptomatic group further complicates the treatment process for this condition.

The interventions with the strongest evidence of treatment efficacy for chronic whiplash are (Center of Trauma and Injury Recovery, 2008):

Poll: https://linkto.run/p/JN2STJZ3

Poll results: https://linkto.run/r/JN2STJZ3

Ward Willaert

Ward Willaert is a doctoral researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Brussels, Belgium) and Ghent university (Ghent, Belgium). He is a member of the Pain in Motion research group and his research and clinical interest goes out to chronic "unexplained" pain, associated disorders, diagnosis and treatment of (chronic) pain. He has a special interest in whiplash associated disorders and the central nervous system.

2020Pain in Motion

References and further reading:

Anstey, R., Kongsted, A., Kamper, S., & Hancock, M. J. (2016). Are People With Whiplash-Associated Neck Pain Different From People With Nonspecific Neck Pain J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 46(10), 894-901. doi:10.2519/jospt.2016.6588

Binder, A. (2007). The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash. Europa Medicophysica, 43, 79-89.

Campbell, L., Smith, A., McGregor, L., & Sterling, M. (2018). Psychological Factors and the Development of Chronic Whiplash-associated Disorder(s): A Systematic Review. Clin J Pain, 34(8), 755-768. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000597

Carroll, L. J., Holm, L. W., Hogg-Johnson, S., Cote, P., Cassidy, J. D., Haldeman, S., Guzman, J. (2009). Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 32(2 Suppl), S97-S107. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.014

De Pauw, R., Coppieters, I., Kregel, J., De Meulemeester, K., Danneels, L., & Cagnie, B. (2016). Does muscle morphology change in chronic neck pain patients? A systematic review. doi:10.1016/j.math.2015.11.006

Delfini, R., Dorizzi, A., Facchinetti, G., Faccioli, F., Galzio, R., & Vangelista, T. (1999). Delayed post-traumatic cervical instability. Surg Neurol, 51(6), 588-594; discussion 594-585. doi:10.1016/s0090-3019(99)00020-8

European_Transport_Safety_Council. [2017-03-13]. Reining in whiplash - better protection for Europe's car occupants. (2007).

Falla, D., Bilenkij, G., & Jull, G. (2004). Patients with chronic neck pain demonstrate altered patterns of muscle activation during performance of a functional upper limb task. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 29(13), 1436-1440.

Holm, L. W., Carroll, L. J., Cassidy, J. D., Hogg-Johnson, S., Cote, P., Guzman, J., . . . Its Associated, D. (2008). The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 33(4 Suppl), S52-59. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643ece

Kamper, S. J., Rebbeck, T. J., Maher, C. G., McAuley, J. H., & Sterling, M. (2008). Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 138, 617-629. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.019

Kamper, S. J., Rebbeck, T. J., Maher, C. G., McAuley, J. H., & Sterling, M. (2008). Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 138(3), 617-629. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.019

Michaleff, Z. A., Maher, C. G., Verhagen, A. P., Rebbeck, T., & Lin, C. W. (2012). Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and NEXUS to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following blunt trauma: a systematic review. CMAJ, 184(16), E867-876. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120675

Miles, K. A., Maimaris, C., Finlay, D., & Barnes, M. R. (1988). The incidence and prognostic significance of radiological abnormalities in soft tissue injuries to the cervical spine. Skeletal Radiol, 17(7), 493-496. doi:10.1007/bf00364043

NICE. Neck pain - whiplash injury. Available from http://cks.nice.org.uk/neck-pain-whiplash-injury (last accessed 26 September 2013)

Partheni M., Constantoyannis C., Ferrari R., Nikiforidis G., Voulgaris S., Papadakis N. A prospective cohort study of the outcome of acute whiplash injury in Greece. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:67–70

Peolsson, A., Karlsson, A., Ghafouri, B., Ebbers, T., Engstrom, M., Jonsson, M., Peterson, G. (2019). Pathophysiology behind prolonged whiplash associated disorders: study protocol for an experimental study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 20(1), 51. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2433-3

Persson, M., Sörensen, J., & Gerdle, B. (2016). Chronic Whiplash Associated Disorders (WAD): Responses to Nerve Blocks of Cervical Zygapophyseal Joints. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.), 17, 2162-2175. doi:10.1093/pm/pnw036

Recovery., C. f. T. a. I. (2008). Clinical guidelines for best practice management of acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders.

Ritchie, C., Hendrikz, J., Kenardy, J., & Sterling, M. (2013). Derivation of a clinical prediction rule to identify both chronic moderate/severe disability and full recovery following whiplash injury. Pain, 154(10), 2198-2206. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.001

Sarrami, P., Armstrong, E., Naylor, J. M., & Harris, I. A. (2017). Factors predicting outcome in whiplash injury: a systematic meta-review of prognostic factors. J Orthop Traumatol, 18(1), 9-16. doi:10.1007/s10195-016-0431-x

Schrader H., Obelieniene D., Bovim G. Natural evolution of late whiplash syndrome outside the medicolegal context. Lancet. 1996;347:1207–1211

Spearing, N. M., & Connelly, L. B. (2011). Is compensation "bad for health"? A systematic meta-review. Injury-International Journal of the Care of the Injured, 42(1), 15-24. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.12.009

Spearing, N. M., Connelly, L. B., Gargett, S., & Sterling, M. (2012). Does injury compensation lead to worse health after whiplash? A systematic review. Pain, 153(6), 1274-1282. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.03.007

Spearing, N. M., Connelly, L. B., Nghiem, H. S., & Pobereskin, L. (2012). Research on injury compensation and health outcomes: ignoring the problem of reverse causality led to a biased conclusion. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 65(11), 1219-1226. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.012

Spearing, N. M., Gyrd-Hansen, D., Pobereskin, L. H., Rowell, D. S., & Connelly, L. B. (2012). Are people who claim compensation "cured by a verdict"? A longitudinal study of health outcomes after whiplash. J Law Med, 20(1), 82-92.

Spitzer, W. O., Skovron, M. L., Salmi, L. R., Cassidy, J. D., Duranceau, J., Suissa, S., & Zeiss, E. (1995). Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining whiplash and its management. Spine, 20, 1S-73S.

State Insurance Regulatory Authority: Guidelines for the management ofacute whiplash-associated disorders – for health professionals. Sydney: third edition. (2014).

Sterling, M., Hendrikz, J., & Kenardy, J. (2011). Similar factors predict disability and posttraumatic stress disorder trajectories after whiplash injury. Pain, 152(6), 1272-1278. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.056

Styrke, J., Stalnacke, B. M., Bylund, P. O., Sojka, P., & Bjornstig, U. (2012). A 10-year incidence of acute whiplash injuries after road traffic crashes in a defined population in northern Sweden. PM R, 4(10), 739-747. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.05.010

Treleaven, J. (2017). Dizziness, Unsteadiness, Visual Disturbances, and Sensorimotor Control in Traumatic Neck Pain. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 47, 492-502. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.7052

Treleaven, J., Peterson, G., Ludvigsson, M. L., Kammerlind, A. S., & Peolsson, A. (2016). Balance, dizziness and proprioception in patients with chronic whiplash associated disorders complaining of dizziness: A prospective randomized study comparing three exercise programs. Man Ther, 22, 122-130. doi:10.1016/j.math.2015.10.017

Ulbrich, E. J., Anderson, S. E., Busato, A., Abderhalden, S., Boesch, C., Zimmermann, H., Sturzenegger, M. (2011). Cervical muscle area measurements in acute whiplash patients and controls. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 33, 668-675. doi:10.1002/jmri.22446

Van Oosterwijck, J., Nijs, J., Meeus, M., & Paul, L. (2013). Evidence for central sensitization in chronic whiplash: a systematic literature review. Eur J Pain, 17(3), 299-312. doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00193.x

Williamson, E., Williams, M., Gates, S., & Lamb, S. E. (2008). A systematic literature review of psychological factors and the development of late whiplash syndrome. Pain, 135(1-2), 20-30. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.035

Wismans KSHM, H. C. (1994). Incidentie en prevalentie van het ‘whiplash’-trauma.

TNO report 94. R.B.V.041. TNO Road-Vehicle Research Institute, Delft